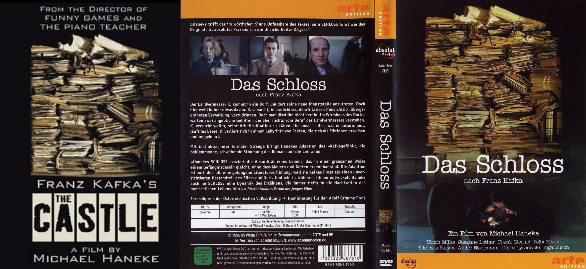

Director: Michael Haneke

Writers: Michael Haneke, Franz Kafka (novel)

Stars: Ulrich Mühe, Susanne Lothar, Nikolaus Paryla

Michael Haneke has left in his wake a series of bleak, quietly disturbing, and serenely harrowing films. From, ‘Funny Games’, to ‘The Piano Teacher’ to that brilliant film that grapples with the wellspring of wickedness and the banality of evil, ‘The White Ribbon,’ the Austrian director has left his mark as someone with an extraordinary degree of perspicacity and insight into the human condition.

Based on the absurdist novel by Franz Kafka, his German language film, ‘Das Schloss’ (The Castle) falls squarely in the middle of the surrealist-absurdist genre of films. In his book, Film as Catharsis, Haneke expresses his disdain for American movies that disempower the viewer by packaging everything nicely for them with neat endings and happily resolved conflicts where the villain always loses and the hero always wins. His films, he elaborates, focus more on leaving the viewer with thought-provoking questions rather than heat-and-eat answers.

If by now alarm bells are ringing in the head of a certain kind of prospective viewer about the plot of Das Schloss, then loud may it resound and long may it reverberate. There’s more to the movie than merely storyline. Ostensibly, the plot revolves around a land surveyor named ‘K’ who through a miscommunication is called to survey the area around a rustic, parochial, and insular village that is suspicious of strangers. The village seems in the thrall of a mysterious castle—which appears to be the bureaucratic headquarters of all administrative affairs in the village. The film chronicles the surveyor’s futile attempts to gain access to the castle—stymied as he is by the bureaucratic obfuscation, general apathy, and hostile dislike of the villagers. Getting to the officials in the castle becomes a matter of supreme importance, but he’s given the run around and has to scramble from pillar to post only to find he’s been moving round in circles.

However, it would be a huge flaw to view the film from only the surface. To truly appreciate the film the viewer is invited to see the metaphor behind the plot and recognise the satire, allegory, and symbols behind the characters and the situation the surveyor finds himself in.

The archetypal themes of isolation and the fundamental loneliness of the individual play out starkly in this film. The black and white sequences, the drab grey scenes, the cold winter setting, the dour, sullen characters, the long static shots, the abrupt scene endings… all come together to allow Haneke to recreate for the big screen that quintessentially Kafkaesque sense of alienation and the absurdity of life from a deeply existential perspective.

One way to view the movie is to see it as man’s effort to make sense of the absurd situation he finds himself in simply through the act of being. The countless obstacles the surveyor finds in his way is symbolic of the numerous frustrations of life that thwart us from attaining our goal. We are all trying to achieve something that we think is important: we strive, we seek, we want, we need… to get something, to do something… and life is just that process—no more. Do we ever really get what we want? We think we know what we want, but do we really?

The castle becomes this symbol of an unattainable goal. The characters in the plot become ‘the others’ –those who do not share in the individual’s pursuit or have no interest in what is of consequence to the individual. Even when the surveyor falls in love—something everyone strives for, and hopes for and dreams about—he soon discovers it doesn’t check his now almost maniacal need to get in touch with the officials in the castle. It brings to mind a quote by Bertrand Russell, “I have sought love, because it brings an ecstasy so great that I would have sacrificed all the rest of my life for a few hours of this joy. I have sought it because it relieves the terrible loneliness – that terrible loneliness in which one shivering consciousness looks over the rim of the world into the cold unfathomable lifeless abyss.” The surveyor has the companionship of a woman who would do anything for him. Yet, he ends up squandering his one chance at freedom and loses the woman because of his obsession with the castle.

The castle and the entire plot may also be viewed along religious lines. The castle may be considered symbolic of god. The bureaucratic hierarchy would be reminiscent of the ecclesiastical power structure, where the believer has to go through priests, bishops, archbishops, cardinals, the pope, and a pullulating plethora of saints, angels, and archangels before reaching god. The quest of the individual to commune with divinity is lost in this ecclesiastical bureaucracy. So, in one way the film is an allegory of the futility of trying to attain the numinous or experiencing the sublime.

This movie is not for all. To truly appreciate its depths and layers of meaning one must have lived; one must have known struggle, known loss, known despair and have found a way out of the depths.