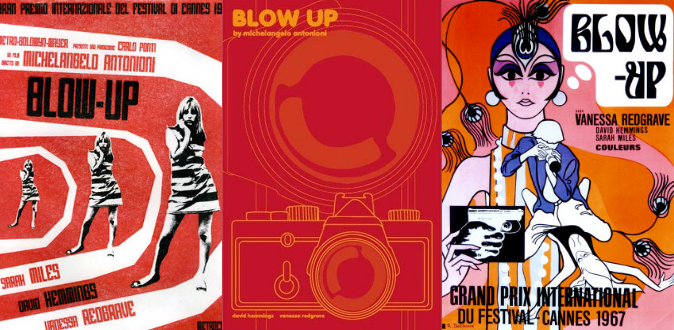

Director: Michelangelo Antonioni

Writers: Based on Julio Cortázar’s short story “Las babas del diablo”

Actors: David Hemmings, Vanessa Redgrave and Sarah Miles

Country: UK

Awards: Cannes Gran Prix

Don’t watch ‘Blow-up’ if you are easily bored. Don’t watch ‘Blow-up’ if you like your hero to ride out into the sunset as the credits roll. Don’t watch ‘Blow-up’ if you prefer your movies Americanised with neat endings, supersized with special effects, and served to you on a platter all neatly packed with a generous portion of McHollywood drama.

However, if you don’t mind exercising your grey cells and actively reflecting on the plot of a movie, then ‘Blow-up’ will be amply rewarding. To strip the movie to its bare storyline would be a vulgar thing to do. However, since it’s the done thing these days to denude a book or a movie and judge it by the curves and contours of its plot, ‘Blow-up’ is essentially about an avant-garde fashion photographer, Thomas (played by David Hemmings) who takes a few innocuous photographs in a public park and later realises he may have unwittingly witnessed and photographed a murder.

A lot of events in the movie wouldn’t make sense unless seen through the voyeuristic prism that director Anotonioni uses to portray the nihilism of 60s youth culture, film as diegesis, and the relationship between art and reality. To the uninformed, unthinking, impatient viewer, the above statement might sound pretentious and perhaps meaningless. But if one is willing to join in the artistic journey, then the movie affords ample scope for discussion and analysis.

The protagonist, Thomas, is a self-obsessed, uncaring, unfeeling photographer who mistreats the women in his life and is bored with his profession. Famous models from the sixties like Veruschka and Jane Birkin make cameo appearances in the film. Thomas makes the archetypal “hero’s journey” over the course of the movie by leaving his mundane, self-obsessed world and being forced to re-examine himself as a photographer/artist. In the end, after his adventure with the mysterious stranger played by Vanessa Redgrave and his strange encounter with a murder that may or may not have happened, he returns with the elixir: a renewed passion and interest in his work.

I believe one of the fundamental messages of the movie is its commentary on art and reality. Art is not reality and can never be. – Simply because there is no one, single, all-encompassing, fundamental, absolute reality. Reality is filtered through the subjective, individual mind; refracted through the prism of personal experiences; and illuminated against the walls of what we call perception. The message of the movie is that on its own Art is nothing; rather, Art is all about what the viewer brings to it.

But one of the points the film makes is that there is a limit to how closely one may analyse art or reality. As Thomas blows-up sections of the incriminating photograph, the idea that a murder might have taken place becomes more and more obvious. However, when the image of the dead body is finally blown-up to maximum, all we see is a grainy, pixelated, washed out image that is not clear. Thomas needs to actually go back to the park to verify what the photo only hints at.

The ending is of paramount importance. Thomas waits for just the right time and lighting to get the perfect shot of the dead body but discovers it no longer exists. The moment is lost forever. The final scene with the mimes playing tennis may seem annoying and prolonged, but it’s the director’s way of allowing the viewer to come to an understanding of the movie. The imaginary ball that Thomas throws back to the mime makes their imaginary game of tennis real. It’s about what Thomas brings to the game: by engaging with the mime artist and being part of the enterprise he makes it real. This idea is reinforced by the sounds of an actual tennis game in progress. Personal perception is all.

Ultimately, the film leaves us in a hall of mirrors – we see the photographs distorted beyond recognition first through the lens of Thomas’ camera but filtered through the lens of Antonioni’s camera. We are twice removed from ‘reality’. Is that, after all is said and done, what art is?