“He has brought a great story out of the shadows.” – Literary Review

“Jim Al-Khalili has a passion for bringing to a wider audience not just the facts of science but its history… Just as the legacy of Copernicus and Darwin belong to all of us, so does that of Ibn Sina and Ibn al-Haytham.” – Independent

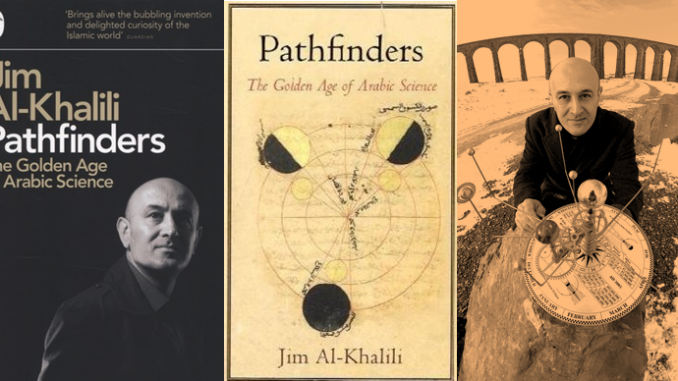

We’re all familiar with the Golden Age of Greece under the aegis of Pericles that saw a flourishing of the arts, philosophy, and architecture in the 5th century BC. Names like Hippocrates, Socrates, Aristosthenes trip lightly off the tongue. We’re also keenly aware of more modern figures like Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton who ushered in the European scientific revolution. However, not many of us are aware of the scientific heroes of the Golden Age of Arabic Science. Jim Al-Khalili’s book Pathfinders sets out to rectify this deficiency in our knowledge base.

At the outset, he is at pains to explain to the reader his decision to refer to the period between the 8th – 12th centuries as the Golden Age of Arabic Science as opposed to Islamic Science. He avers there can no more be Islamic Science than there can be Jewish Science or Christian Science. He points out that many of the great figures of the Golden Age were not necessarily Muslim – there were Jewish figures and Christian figures as well (mostly from the Nestorian and Monophysite sects) who were part of this Golden Age. He prefers to call it Arabic Science because the language in which their work was published was Arabic – regardless of whether they were of Persian or Spanish ethnicity.

One of the theses the books sets out to present to the reader is the idea that the great scientists of the European scientific revolution from the 17th century onwards owe a debt to the proto-scientists of the Golden Age of Arabic Science that took place several centuries before. He refers to these figures as proto-scientists because in contrast to the ancient Greeks who favoured the power of ideas and pure thought these Arabic scientists favoured observation and measurement. Evidence was an important component of their practice. However, they were “proto-scientists” because they didn’t follow the rigorous process of the modern scientific method. Much of their science was mixed with religious beliefs and the occult.

Al-Khalili points out that the Golden Age of Arabic science had its origins in 8th Century Baghdad under the Abbasid dynasty. During this period, Islam influenced scientific and philosophical thinking to a great extent and was driven by the need of early scholars to interpret the Quran. The political climate in Baghdad at the time was dominated by a movement of Islamic rationalists, known as Mu’tazilites, who sought to combine faith and reason. This led to a spirit of tolerance in which scientific enquiry was encouraged.

Just as the birth of the European Renaissance had much to do with the Medici family’s patronage, the birth of the Golden Age of Arabic Science had much to do with the early Abbasid kings, Al-Rashid and his son Al-Ma’mun, who encouraged translations of books into Arabic from Greek, Sanskrit, and Persian. The Bayt-Al-Hikma (The House of Wisdom) was one of the most prominent libraries of the Golden Age and Baghdad itself became a global centre of knowledge and learning.

The book gives the reader an overview of the history of the Arab world at the time, the rise and spread of Islam, and devotes a separate chapter for each of the key scientific figures of this period, including, Al Khawarizmi, the mathematician, Al Haytham, the physicist, Al-Biruni, the polymath, Ibn Sina, the medical practitioner, and Al-Razi, the alchemist, among many others. He also charts the course of the spread of Arabic science through the Fatimid dynasty in Cairo and on to the Ummayad dynasty in Spain.

The book offers a brief analysis of why the Golden Age of Arabic Science came to an end. There were several reasons for this – the sacking of Baghdad by the Ottomans in the 13th century, the destruction of Cordoba in Spain around the same time, and the rise of a more conservative interpretation of Islam that looked upon scientific investigation with suspicion. But the most important reason for the end of the Golden Age was the debilitating slowness with which the Arabic world embraced the printing press.

Al-Khalili concludes by offering a dismal overview of the state of Arabic science today: Muslim countries have on average 10 scientists per 1,000 members of their population (in contrast to 140 in the developed world). They contribute only 1% of published scientific papers. Indeed, the number of all the scientific papers published in the Muslim world is less than what the Harvard University alone publishes.

What makes Pathfinders such an enlightening read is that it gives the reader insight into a period and movement that many of us are unaware of. The book highlights the huge strides made in the Middle East in the fields of Astronomy, Chemistry, Medicine, and Mathematics. From Algebra to Trigonometry to the names of the brightest stars in the constellations, the debt the rest of the world owes the Arabic scientists of the Golden Age is significant. This book is essential reading for lovers of science and offers the reader hope that if the Middle East was once able to contribute so much to the field of science then perhaps it can do so again.