What the human species faces at this point is primarily a crisis of perception. Many of the global challenges we face arise out of a fundamentally problematic understanding of reality that is harming the biosphere and human life in alarming and perhaps irreversible ways. The living world is in peril and we are too self-absorbed to foresee the long-term consequences of our actions. Our leaders are unable or unwilling to see that many of the problems we face are interconnected and interdependent – in other words, our problems are systemic. The need of the hour is a social and scientific paradigm shift. This is precisely what Fritjof Capra sets out to elucidate in his book, The Web of Life.

Capra defines this paradigm shift as “a constellation of concepts, values, perceptions, and practices shared by a community, which forms a particular vision of reality that is the basis of the way the community organises itself.”

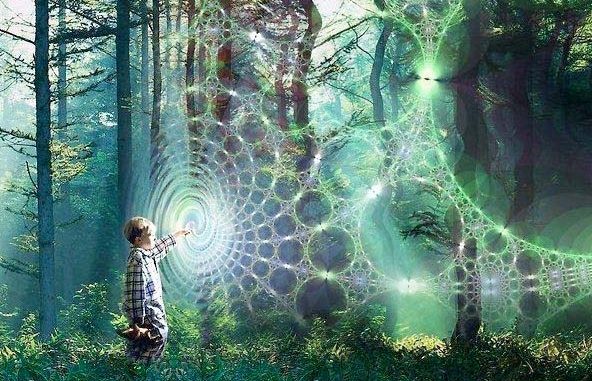

This new paradigm essentially involves taking a holistic worldview and accepting the interconnectedness of the world as an integrated whole as opposed to a dissociated collection of parts.

In the Web of Life, Capra offers a scintillating synthesis of scientific breakthroughs in cybernetics, information theory, chaos theory, Gaia theory, and systems thinking, all the while expatiating on a deep ecological vision of reality.

Capra’s contention is that the basic tension is one between the parts and the whole: between a mechanistic, reductionist, or atomistic worldview and a holistic, organismic, or ecological worldview. The latter perspective has now come to be known as “systems thinking” which, in essence, is what much of the book is about.

Systems thinking may be understood in terms of connectedness, relationships, and context. According to the systems view, the essential properties of an organism or living system, are properties of the whole, which none of the parts has. They arise from interactions and relationships among the parts.

Systemic properties are destroyed when a system is dissected into isolated elements. And herein lies the crux of much of what assails modern society. Our inability to see that what we call a part is merely a pattern in an inseparable web of relationships is causing deep and profound harm to ourselves psychologically and to our environment ecologically.

Capra avers that in this new systems thinking, the metaphor of knowledge as a building is being replaced by that of the network. Once we accept this, we realise everything is connected to everything else, and there are no foundations. Such a perspective, if widespread, would have a tremendous bearing on how we relate to one another and to our environment.

In the book, Capra also elaborates on the various patterns evident in life, the mathematics of complexity, feedback loops, non-linearity, fractal phenomena, laser theory, hypercycles, dissipative structures, and perhaps most importantly, on the concept of autopoiesis – the self-organisation of living systems.

Capra, who’s a renowned author, is the founding director of the Center for Ecoliteracy in Berkeley, California. The central thesis in his various books has been that “a theory of living systems consistent with the philosophical framework of deep ecology, including an appropriate mathematical language, and implying a non- mechanistic, post-Cartesian understanding of life is now emerging.”

The final sections of The Web of Life conclude with a provocative and beguiling theory of living systems in which mind is seen not as a thing but as a process – the very process of life. In other words, the organising activity of living systems, at all levels of life, is mental activity. The interactions of a living organism with its environment are cognitive, or mental interactions. Thus, life and cognition become inseparably connected. And Mind is immanent in matter at all levels of life – in individual organisms, in ecosystems, and in social systems.

This is undoubtedly a radical and controversial reimagining of our traditional understanding of the process of life and our theories of mind. But if we are to have even a ghost of a chance at fixing the enormous global challenges we face, then such radically new conceptions of reality are just what we need.

Ilya Prigogine, the Romanian chemist and physicist, remarked, “The world we see outside and the world we see within are converging. This convergence of two worlds is perhaps the most important cultural event of our age.”

This thought-provoking and mind-expanding book provides the reader with a conceptual framework for the link between ecological communities and human communities. Humanity now faces a major clash between ecology and economics. This clash arises from the fact that nature is cyclical, whereas our industrial systems are linear. Our businesses take resources, transform them into products plus waste, and sell the products to consumers, who discard more waste when they have consumed the products. This is simply not sustainable.

Capra points out that “corporate economists treat as free commodities not only the air, water, and soil, but also the delicate web of social relations, which is severely affected by continuing economic expansion. Private profits are being made at public costs in the deterioration of the environment and the general quality of life, and at the expense of future generations. There is a lack of basic ecological literacy.”

We need to fundamentally redesign our businesses and economies. Taking a systemic and holistic perspective based on deep ecology is one important way to do it.

Capra concludes his book by reminding us of the importance of ecological literacy and that to regain our full humanity, we have to regain our experience of connectedness with the entire web of life.